First look at model-based reinforcement learning MBRL

Many reinforcement learning algorithms are model-free. They optimize a policy and/or value network without explicitly trying to learn aspects of the environment dynamics. Model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL) algorithms can be more sample efficient, making them cheaper to train. However, they may converge to poorer solutions than model-free methods (Chua et al. 2018). MBRL methods are still an attractive approach if difficulties with using a learned model can be overcome. They offer better sample efficiency and the ability to conduct long-term planning, evaluating candidate trajectories.

Training an agent and environment model together has additional challenges on top of those for training an agent alone. For example, if the planning model has never seen a region of the environment, its predictions may be invalid affecting the agent’s choice of trajectories. Complex environments also present other challenges like local minima, changing environments, and stochasticity (uncertain future states/rewards that cause difficulty for accurate planning) (Boney et al. 2019).

It would make sense for MBRL to outperform model-free methods if these problems are overcome given the additional, human-like, capability to consider what will happen in the future given a particular action.

MBRL methods can utilize either a known model or a learned model. AlphaGo, AlphaGo Zero, and AlphaZero all planned using an encoded model of the game. However, it may not be possible or feasible to encode all of the rules or dynamics of an environment. The major advancement of MuZero is the transition to planning with a learned model where the agent has to discover the rules and dynamics of the game (Schrittwieser et al. 2020). Mastering this technique means that a single algorithm can be applied to many environments.

Variations of MBRL

A variety of approaches for integrating a model into reinforcement learning. These can range from a straight-forward state transition approach that predicts the next state and/or reward given the current state and action,

\[r, s_{t+1} = f(s_t, a_t)\]to inverse or backward models that learn what action occurred to transition the state from one step to the next,

\[a_t = f(s_t, s_{t+1})\]and even approaches that predict the expected future return and current reward.

These models can also be implemented in different ways. For example, model predictive control (MPC) is a closed-loop control approach that attempts to find an optimal trajectory to follow using a model. Typically this involves exploring several candidate trajectories a set timespan into the future, evaluating which has the highest predicted reward, and executing the first action in the optimal trajectory. Then the process starts over, repeating the explore, evaluate, step sequence until the episode terminates. With an accurate model and a good strategy for selecting actions (cross-entropy method for example), this approach can succeed in simpler environments even without an RL agent like PPO or DQN (Chua et al. 2018).

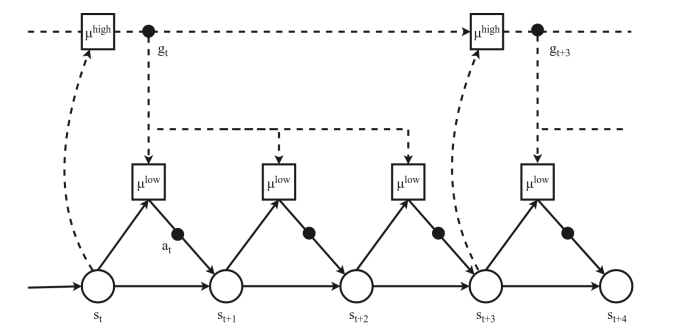

MBRL can also be split into different planning levels such as the hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) approach in Nachum et al. (2018). This method uses a high-level agent responsible for long-term planning while a low-level agent executes actions under the chosen branch or trajectory.

Hierarchical reinforcement learning (source: Moerland, Broekens, and Jonker 2021)

It’s also possible to train an agent with little to no real environment data using a learned model of the world. This effectively converts the MBRL problem into model-free RL in a learned model.

Training in a world model

All of this makes for an intriguing area to explore. I decided to start by developing a proximal policy optimization (PPO) implementation in a learned model similar to the SimPLe algorithm in Kaiser et al. (2020).

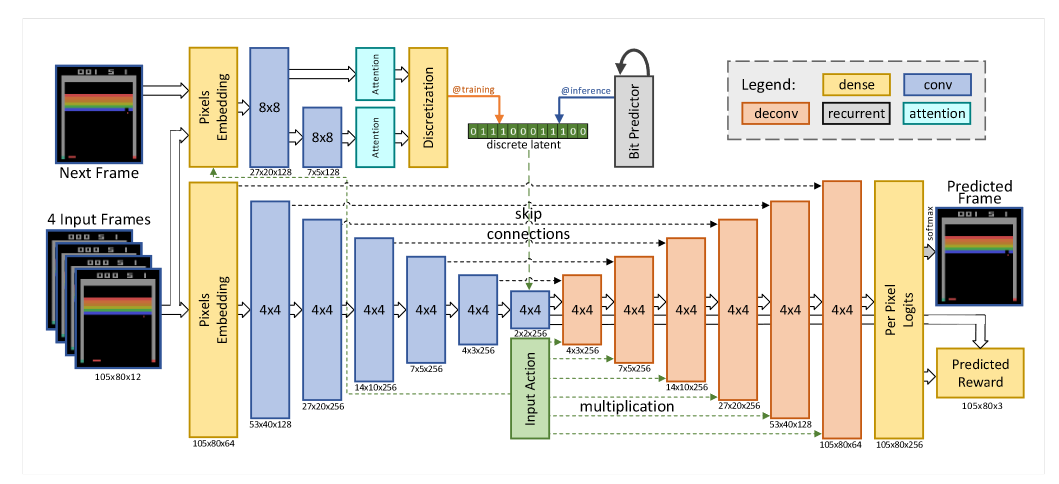

Training in learned Atari, SimPLe

They used a combination recurrent and convolutional architecture to take four input frames and predict the next frame and reward. Their agent learned in this world model which was occasionally synced with the real world. If the model can accurately represent the real world, most of the PPO agent learning can be done within the model rather than in the real world.

(Kaiser et al. 2020)

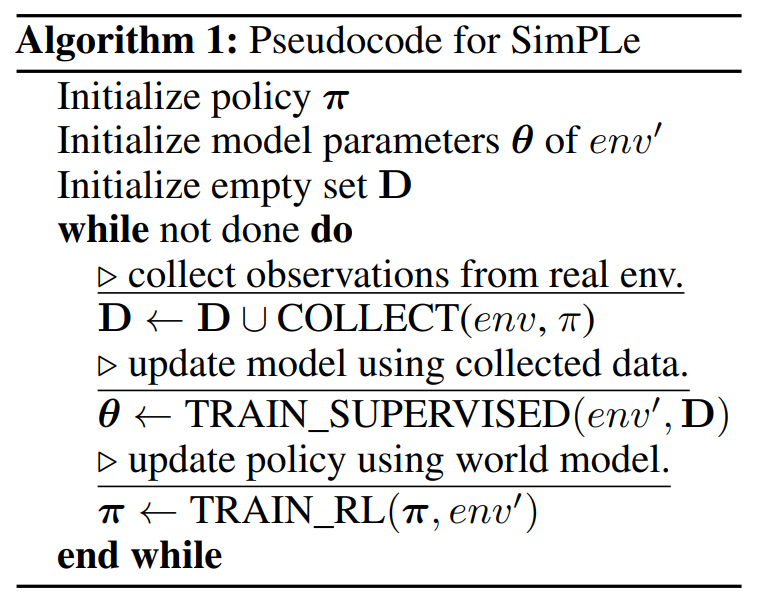

Here is the SimPLe algorithm from Kaiser et al. Real environment data is used to update the world model, then the world model is used to train the policy. Occasionally, the authors reset the simulated environment to the real state to help reduce the compounding of errors in the world model.

(Kaiser et al. 2020)

OpenAI gym lunar lander

Instead of passing a sequence of frames to the model, I’m using the current state vector from the OpenAI gym environment, Lunar Lander. In Lunar Lander, the objective is to control a descending spacecraft to a soft landing on the surface of the moon by controlling thrust and rotation. The state and action combine to form the model input and the target is to predict the next state vector and reward. Otherwise, my approach follows the basic outline of SimPLe in Kaiser et. al (2020).

You might ask why not learn and then integrate the derivative of the state transition in a recurrent model or directly with an ODE? This is probably a good next approach (and something on my list to try) since the world model had difficulty learning the entire state/action/reward space.

Results

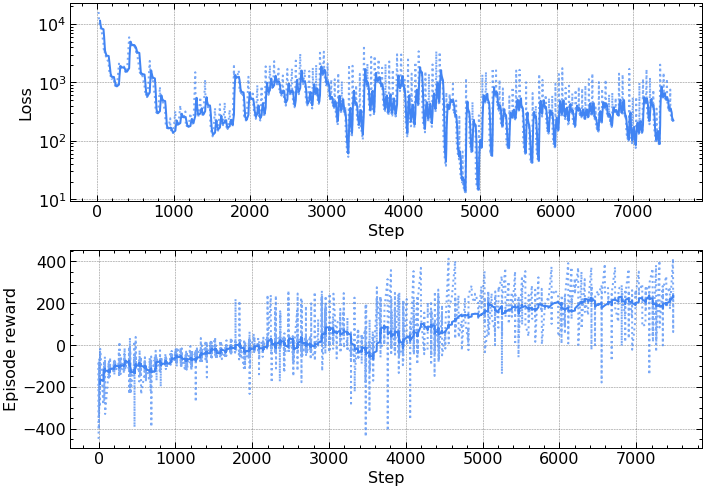

Training a PPO agent to succeed in Lunar Lander is fairly straightforward (see this post). However, training the agent while learning the model concurrently is more challenging. The plot below is typical performance for model-free PPO on the Lunar Lander environment with default hyperparameters from Schulman et al. (2017).

Model-free PPO performance in Lunar Lander

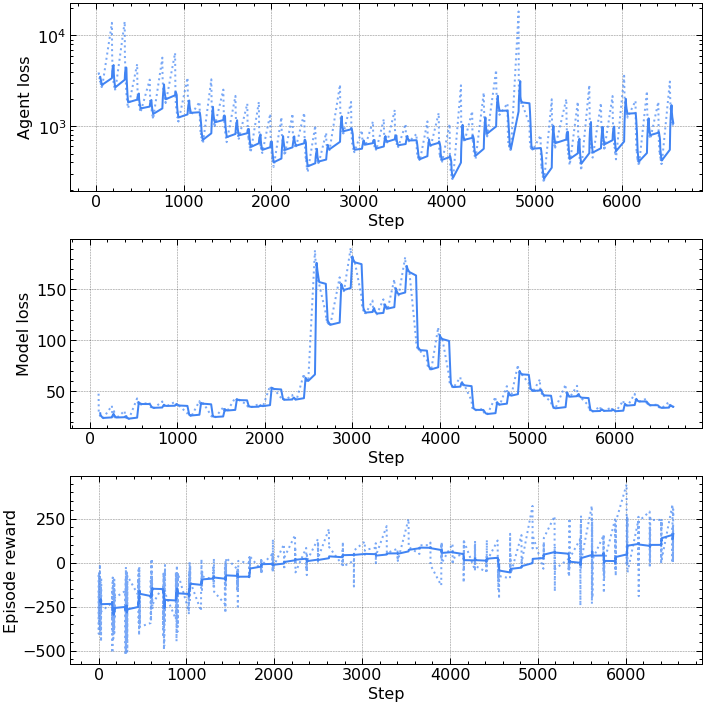

The plot below is one of the better performing runs trained in the learned model. The MBRL approach was extremely sensitive to hyperparameters and even the random starting conditions, not performing consistently across runs even with the same settings. The agent typically fell into a local optimum achieving rewards of ~100, but never consistently achieving rewards of around 200 which is considered solved for this environment.

PPO in a learned model performance

The accuracy of the world model has a huge impact on the performance of the agent. If the model is poor, it can cause the policy to move in an unfavorable direction. The agent’s rapid initial improvement can suddenly be followed by a collapse in model accuracy and agent reward.

Hyperparameters

One of the challenging aspects of MBRL is hyperparameter tuning. Since the model and the agent have to be trained together, both sets of hyperparameters have to be tuned precisely to keep their training in balance. One reason RL is difficult, in general, is because of shifting targets, but when training in a learned model, the rewards themselves also move as the model learns.

However, it’s not just that the hyperparameters need to be balanced. The optimal set of parameters might change during training (Lambert et al. 2021). Models with planning can take advantage of this by adjusting their planning horizon as the model becomes more accurate:

When the distribution of the data we are using changes over time, we look to dynamic hyperparameter tuning where the hyperparameters of the model or optimizer are adapted over time. In the case of MBRL, this can have an elegant interpretation: as the agent gets more data, it can train a more accurate model, and then it may want to use that model to plan further into the future. This would translate to a dynamic tuning of the model predictive horizon hyperparameter variable used in the action optimization. Static hyperparameters – which most RL algorithms report in tables in the appendix of their papers – are likely not going to be able to deal with shifting distributions. (Lambert et al. 2021)

Exploration and epistemic uncertainty

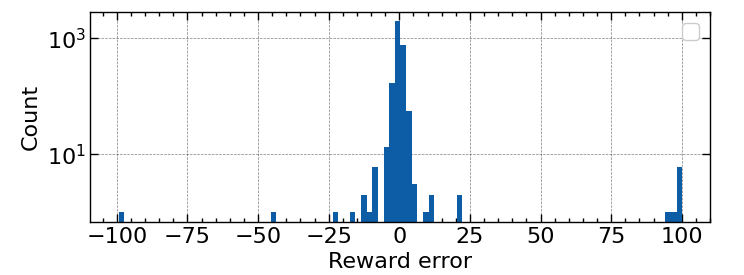

The Lunar Lander environment has the largest reward (+100) for successfully touching each leg of the lander on the ground within the goal. This large reward so late in the episode is difficult to model effectively and can cause the agent to get stuck in local optima. The lander flies around until the episode terminates, never crashing but also never landing. An approach that accounts for the model inaccuracy in this region of the environment (epistemic uncertainty) by marking it as less reliable until properly explored should help the agent discover a better global optimum (Boney et al. 2019).

Many of the transition rewards are well modeled but the model struggles with rarely seen rewards even when normalized

A simple method to increase exploration is to adjust the actor logits before computing the distribution. Lowering all of the logits by a scale factor causes the actor to choose low probability events slightly more often which is appropriate given the model’s inaccuracy early in training. This causes the actor to behave slightly more randomly, increasing exploration. Encouraging more exploration may also help later in training when the agent reward appeared to plateau, allowing it to escapade from local optima.

Final thoughts

This experiment illuminated many of the difficulties in MBRL, and why it’s crucial to both learn an accurate model of the environment but also be able to monitor which regions of the environment are modeled and accurately, balancing the exploration of poorly understood areas with exploiting known good paths.

A few things I’m interested in trying:

- Recurrent environment model - learn the change between states rather than the new state directly

- Model ensembles - use multiple models to try and quantify prediction uncertainty.

- Autoencoder regularization - use an autoencoder to determine which trajectories are outside the training distribution and not accurately modeled (Boney et al. 2019).

- Dynamic hyperparameters - adjust hyperparameters while training rather than starting from a fixed set.

- Learn and implement in JAX and the associated packages built on top of it by DeepMind.

Link to the code for this article. Check out this Machine Learning Street Talk episode on model-based RL!

See something wrong or have a question? Contact me or message me on Twitter. (I’m thinking of adding comments to the site but in a way that doesn’t add a bunch of trackers.)

References

- Boney, Rinu, Norman Di Palo, Mathias Berglund, Alexander Ilin, Juho Kannala, Antti Rasmus, and Harri Valpola. “Regularizing Trajectory Optimization with Denoising Autoencoders.” ArXiv:1903.11981 [Cs, Stat], December 25, 2019. http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.11981.

- Chua, Kurtland, Roberto Calandra, Rowan McAllister, and Sergey Levine. “Deep Reinforcement Learning in a Handful of Trials Using Probabilistic Dynamics Models.” ArXiv:1805.12114 [Cs, Stat], November 2, 2018. http://arxiv.org/abs/1805.12114.

- Hafner, Danijar, Timothy Lillicrap, Mohammad Norouzi, and Jimmy Ba. “Mastering Atari with Discrete World Models.” ArXiv:2010.02193 [Cs, Stat], May 3, 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.02193.

- Kaiser, Lukasz, Mohammad Babaeizadeh, Piotr Milos, Blazej Osinski, Roy H. Campbell, Konrad Czechowski, Dumitru Erhan, et al. “Model-Based Reinforcement Learning for Atari.” ArXiv:1903.00374 [Cs, Stat], February 19, 2020. http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.00374.

- Lambert, Nathan, Baohe Zhang, Raghu Rajan, and André Biedenkapp. “The Importance of Hyperparameter Optimization for Model-Based Reinforcement Learning.” The Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research Blog, 2021. https://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2021/04/19/mbrl/.

- Moerland, Thomas M., Joost Broekens, and Catholijn M. Jonker. “Model-Based Reinforcement Learning: A Survey.” ArXiv:2006.16712 [Cs, Stat], February 25, 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.16712.

- Mordatch, Igor, and Jessica Hamrick. “Tutorial on Model-Based Methods in Reinforcement Learning.” 2020. https://sites.google.com/view/mbrl-tutorial.

- Nachum, Ofir, Shixiang Gu, Honglak Lee, and Sergey Levine. “Data-Efficient Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning.” ArXiv:1805.08296 [Cs, Stat], October 5, 2018. http://arxiv.org/abs/1805.08296.

- Pascanu, Razvan, Yujia Li, Oriol Vinyals, Nicolas Heess, Lars Buesing, Sebastien Racanière, David Reichert, Théophane Weber, Daan Wierstra, and Peter Battaglia. “Learning Model-Based Planning from Scratch.” ArXiv:1707.06170 [Cs, Stat], July 19, 2017. http://arxiv.org/abs/1707.06170.

- Schrittwieser, Julian, Ioannis Antonoglou, Thomas Hubert, Karen Simonyan, Laurent Sifre, Simon Schmitt, Arthur Guez, et al. “Mastering Atari, Go, Chess and Shogi by Planning with a Learned Model.” Nature 588, no. 7839 (December 24, 2020): 604–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03051-4.

- Schulman, John, Filip Wolski, Prafulla Dhariwal, Alec Radford, and Oleg Klimov. “Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms.” ArXiv:1707.06347 [Cs], August 28, 2017. http://arxiv.org/abs/1707.06347.

- Zhang, Baohe, Raghu Rajan, Luis Pineda, Nathan Lambert, André Biedenkapp, Kurtland Chua, Frank Hutter, and Roberto Calandra. “On the Importance of Hyperparameter Optimization for Model-Based Reinforcement Learning.” ArXiv:2102.13651 [Cs, Eess], February 26, 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.13651.